An exercise in using history to create fiction. “After all, the history we get is reconstructed from letters, hearsay, newspapers, archaeology, and so on—sounds like writing fiction from multiple sources!”

Novakovich, Josip. Fiction Writer’s Workshop (p. 23). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Deborah fastened a ribbon around the high neck of her modest, mended gown and resolved to go through with her plan.

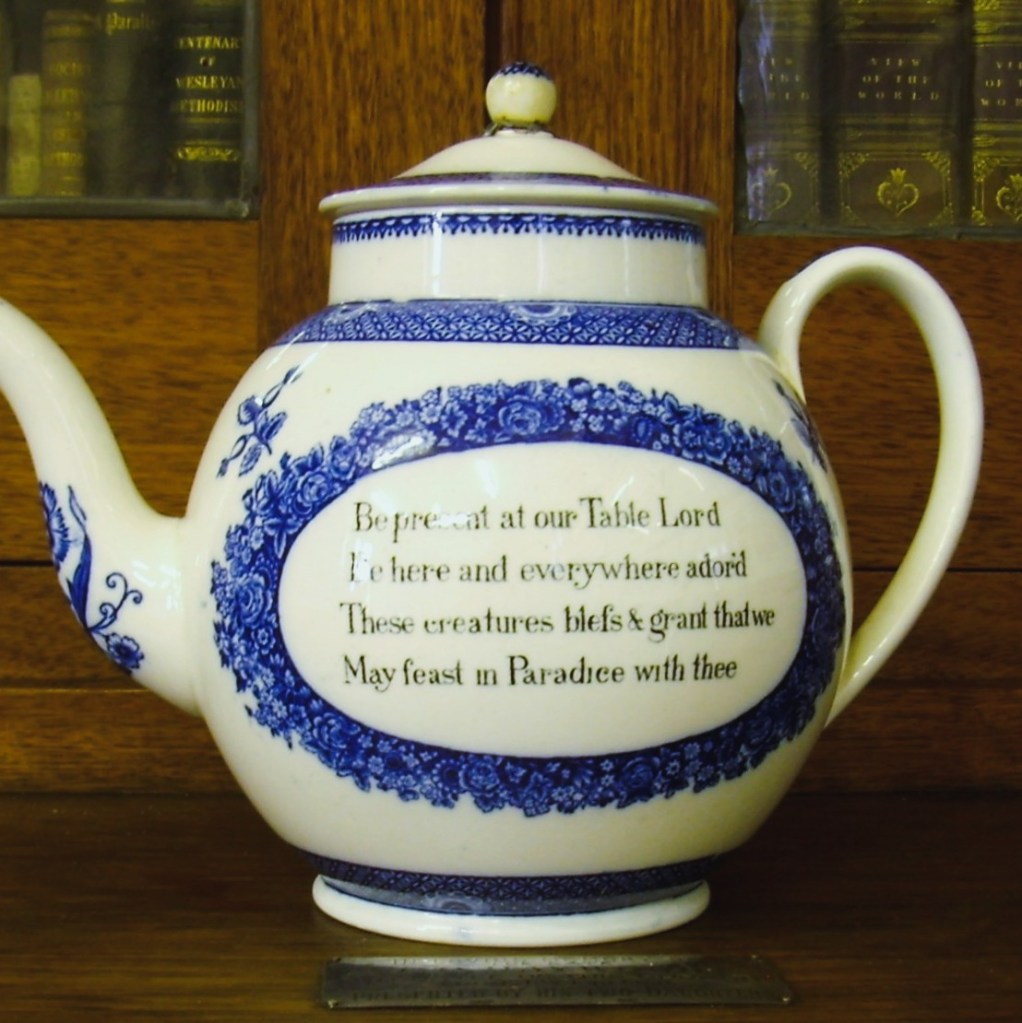

It would be a big occasion in the small history of the Methodist Connexion at Hobart, in Van Diemen’s Land, in 1825. The Tea Meeting would commence precisely upon the hour at four, when the worst heat of the day would be subsiding. Her husband, Benjamin, would give a sermon on the virtues of reading and the improvement of moral character. The Deputy Lieutenant-Governor would attend – the greater man, the Lieutenant-Governor himself, having declined, regretfully, due to a prior engagement. The last preparations were being made as the Guild Ladies set out the refreshments under covers – for the bush flies were still bad. They were always bad for a few weeks after the lambing.

The idea of a Public Library “for the improvement of character and morals” of the penal colony’s residents had, at first, seemed laughable. But through the persistence of Benjamin and Deborah – its chief promoters – it had begun to take shape, at first, with a public meeting, which had raised the sum of ten pounds – enough to purchase a subscription to The Wesleyan Magazine as well as to The Christian Miscellany and Family Visitor – though they would take months to reach Van Diemen’s Land by ship travelling via the Cape of Good Hope across the Southern Ocean.

After that, the town’s worthies – hoping perhaps to be memorialised by the elaborate donor bookplates – and even some of the ticket-of-leave men, mostly of the better sort, re-establishing themselves in the elastic society of the town – began to donate books they had somehow acquired themselves.

But “nothing frivolous or pernicious”. That was the first rule of the Library, and it was rigorously enforced at Trust meetings, where books which had been put up for acquisition were scrutinised before being approved or rejected. “Science would be regarded”, but it would be regarded “only as the handmaid of religion” – and, whilst Benjamin had fought to ensure that “Man, his great Author, and the vast Universe should be surveyed”, Deborah had worked hard to persuade her husband to extend the collection to the field of biography. Who knew what dark secrets might be revealed in stories of the good and great – especially if they be stories of those who had only recently risen to greatness, and therefore goodness, in the penal colony! It would have to be supervised closely – and held in a restricted section, perhaps.

Nevertheless, the collection continued to grow, Benjamin even contributing fifty of his own books and twenty pounds from household funds. They had felt that! And Deborah had been the one responsible for economising, whilst Benjamin met, with pained bewilderment, the rebuke for overspending administered by the London Society.

The Library would open and Benjamin would act as its Librarian, signing out the first books to eager borrowers this very evening. Yet, there was one book which the library had not acquired. It was Deborah’s copy of a volume of “Addison’s Works” – the Third Volume – presented to her on her departure from Gravesend six years earlier. It had travelled with her through storm and fire and childbirth and had brought her the comfort of a connection to Home. Benjamin had asked her if she might offer it, for it contained the edifying “Cato” and could do much to contribute to the moral improvement of the Colony. But how could she part with it? What if it were to be rejected by the Trust at Quarterly Meeting? That would bring shame and humiliation upon her and her husband.

Though what if, she thought, it were to appear mysteriously – almost as by some miracle of the Unknown Stranger? Who among the Trustees, seeing it amongst the collection, could gainsay its virtue? It needed not approval or disapproval – only presence. She whispered to herself the remembered lines: “Here will I hold. If there’s a power above us… He must delight in virtue; And that which He delights in must be happy.”

She would go through with it. She needed no bookplate acknowledgment. She and Benjamin would know from whence it came – the gift of her heart to the town, her home now. She smiled as the lines again came to her, “Content thyself to be obscurely good … the post of honour is a private station.”

Deborah fastened a ribbon around the high neck of her modest, mended gown. She gathered the volume under her apron – worn this evening for service – stepped outside, and slipped into the Library before anyone should notice.

Leave a reply to Remembering the Wesleyan Library: 200 Years after Its Establishment at Hobart Town – Heritage People Cancel reply