A writing exercise in giving one intense emotion I’ve experienced [anger] to a fictional character. I had to make sure the character is not me, but the emotion should be mine. The task required me to create a scene employing the fictional character and the emotion and to involve another person as an antagonist or a co-protagonist.

Novakovich, Josip. Fiction Writer’s Workshop (p. 23). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Boarding school life was always unsettled in the first few weeks of a new year, and especially so for boys transitioning into Year 8, when they were introduced to the curriculum and methods of the Senior School.

It was a turbulent time for the pupils – many of them new in from the Bush or the Islands and wearing uniform for the first time. Even for boys who had come up through the Junior School and had stayed on there as experienced leaders in the Lower House, it was a challenging time, as a new social order was worked out in class, in the House, and on the sporting fields.

In Southeast Queensland in early February, it was still hot, and boys who had spent their summer in shorts and thongs adjusted to the discomfort of leather shoes, long woollen trousers, long-sleeved shirts and woollen ties. First period in the afternoon was the worst: boys, having returned from cricket nets, were sweating – some mature enough in young manhood to smell bad, others with the hot dining room lunch sitting heavily and disagreeably in their bellies.

This was the condition in which 8A assembled for their Geometry lesson one humid afternoon, to await the commencement of class.

The Master – tall and lean, black gown billowing and with cane in hand – burst into the room, announcing his power and presence. The boys instantly rose and stood to attention, each staring at the sweat-soaked shirt in front of him, and silent until the Master should speak. Springing to the podium, he turned.

“Good afternoon, gentlemen.”

“Good afternoon, Sir,” they replied.

“Sit.”

On the command, the boys sat – some of the less experienced dragging their chairs across the dusty wooden floor.

“Take out your books and prepare to write.”

The boys, following their drill, lifted the lids of their desks, produced text and daybooks, took out writing tools, and filled the old-fashioned ink wells. The smell of Quink Washable Royal Blue mingled with the stuffy air.

The Master, inspecting their preparations, surveyed each boy in turn.

“Beaton,” he said, picking out one of the new boys.

Beaton stood.

“Fasten your tie,” ading with malice – as though the simple direction were not enough. “You’re in school now, not in some trashy public bar.” Beaton’s family were hoteliers. “Is that how your father told you you could wear your tie?”

Beaton – red-faced from heat or humiliation – had to reply, for no question asked by a Master was ever merely rhetorical. He mumbled:

“N… No.”

“No what?” growled the Master.

“No, Sir,” Beaton replied.

“Then get on with it.”

That was the signal for Beaton to do as he had been told. He sat, fastened the too-tight button, and adjusted his tie, as the Master turned to the blackboard and began to write a theorem.

Beaton – new and unschooled in the ways of Masters – must have felt the ordeal was over. While the Master wrote, he bent down – as though to retrieve something that had dropped to the floor – and secretly unfastened his collar, loosening the tie only slightly for comfort and in hope that he might escape notice.

But boys’ eyes and ears are sharp. At his rising, a sudden intake of breath from one neighbour, a snigger from another, drew attention to Beaton’s unwitting insolence. Boys stirred.

The disturbance was enough to catch the Master’s attention. He turned.

Those who had moments earlier been watching Beaton – whether in admiration or horror – snapped their heads forward. But not quickly enough. The Master, as though by some supernatural geometry, traced the angles of their sightlines and fastened his gaze upon poor Beaton.

His voice, when it came, seethed with the menace of accusation.

“Beaton, you have disobeyed me.”

“I… I was hot,” retorted Beaton – seeking justification, but forgetting again to say “Sir”, and thinking only of his own comfort.

There were rules for punishing disobedience – formal punishments beyond the usual types of incidental and discretionary violence permitted to masters in their own classrooms. The Headmaster could administer six strokes of the cane across the buttocks of any boy deserving of punishment; House Masters, four; and an ordinary master could give two “of his best”.

Rules for disobedience – but no rules for insolence.

The Master appeared to weigh them up and, in an instant, to abandon them. Reddish complexion darkening, he seized his cane in his left hand and – with knuckles whitening – leapt from the podium in a reckless descent upon the panicked boy.

Lo! He comes in clouds of thunder.

Scattering furniture and school bags, he was on Beaton in a flash, grabbing him by his shirtfront and flinging him forward across his desk.

One. Two. The strokes came.

The punishment administered, Beaton cried out as the Master forced his head against the desk.

Three. Four. The fourth – misaimed – fell across Beaton’s back.

Surely it must end now.

“I’ll show you ‘hot’, wee Beaton!” shouted the Master, white spittle forming at the corners of his mouth.

Beaton struggled to gain his balance as the Master dragged him from his seat as if to throw him outside. He tried to run to the back of the room. The Master held to Beaton’s ink-stained shirt. It ripped – the red welt from the fourth stroke now revealed to all.

Mercilessly, the Master continued to cane poor Beaton – on his back, his legs, his arms – whilst 8A sat shocked but silent, as one of their fellows – for poor Beaton, having endured such punishment, must now from pity be a “fellow” – was flogged.

Beaton, at length subdued, crumpled against the back wall of the classroom. The Master left him there. There would be no nurse, no gentle hand to soothe his wounds.

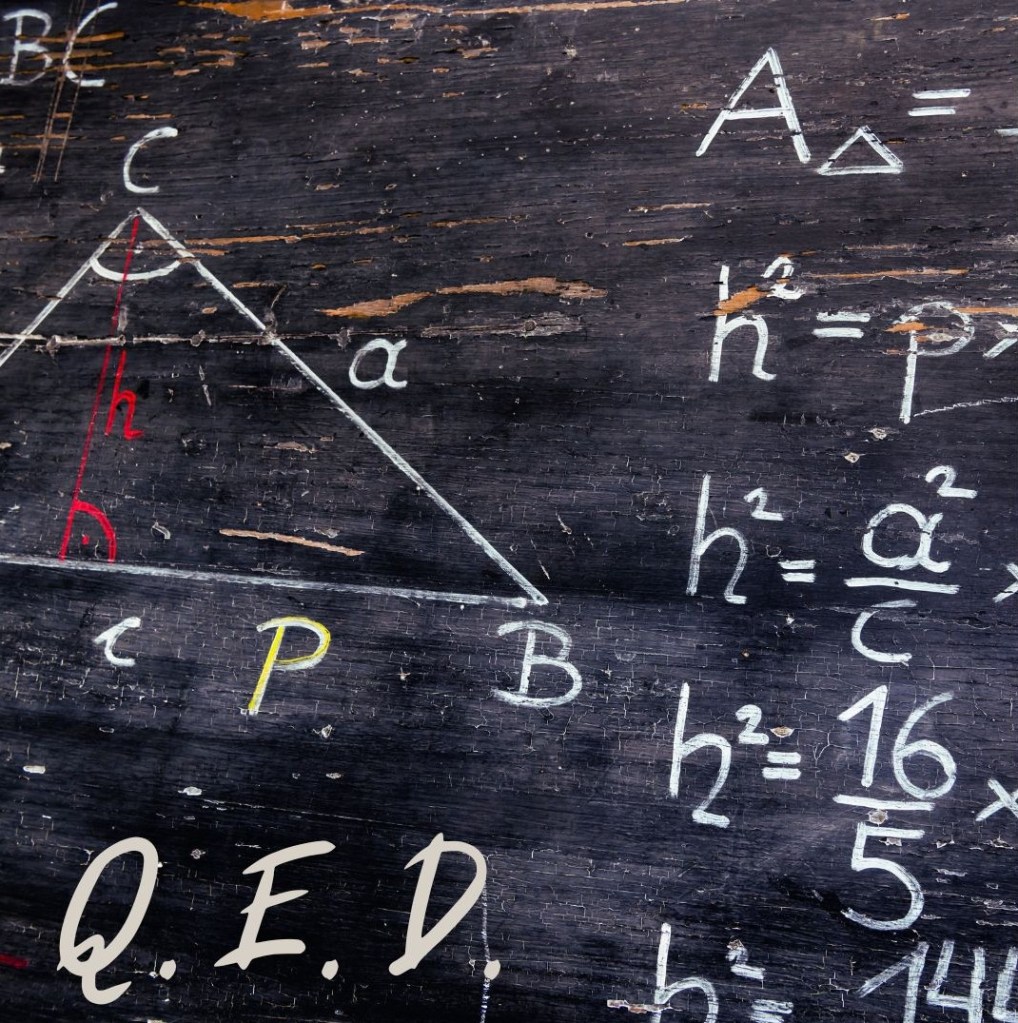

The Master returned to his podium, turned to his blackboard, and completed his theorem with a flourish.

Q.E.D.

Leave a comment